Cigarette plain packaging: Beware unintended outcomes

Simon discusses the benefits and drawbacks of plain packaging of tobacco products.

There no longer needs to be a discussion on whether or not smoking is bad for health. The conversation is instead focusing is the issue of plain packaging, which some believe will help reduce smoking rates. Unfortunately, the best intentions count for little as it is the outcomes that matter – and there is the distinct possibility that any such exercise could backfire if smokers are actually looking for the deleterious effects of tobacco.

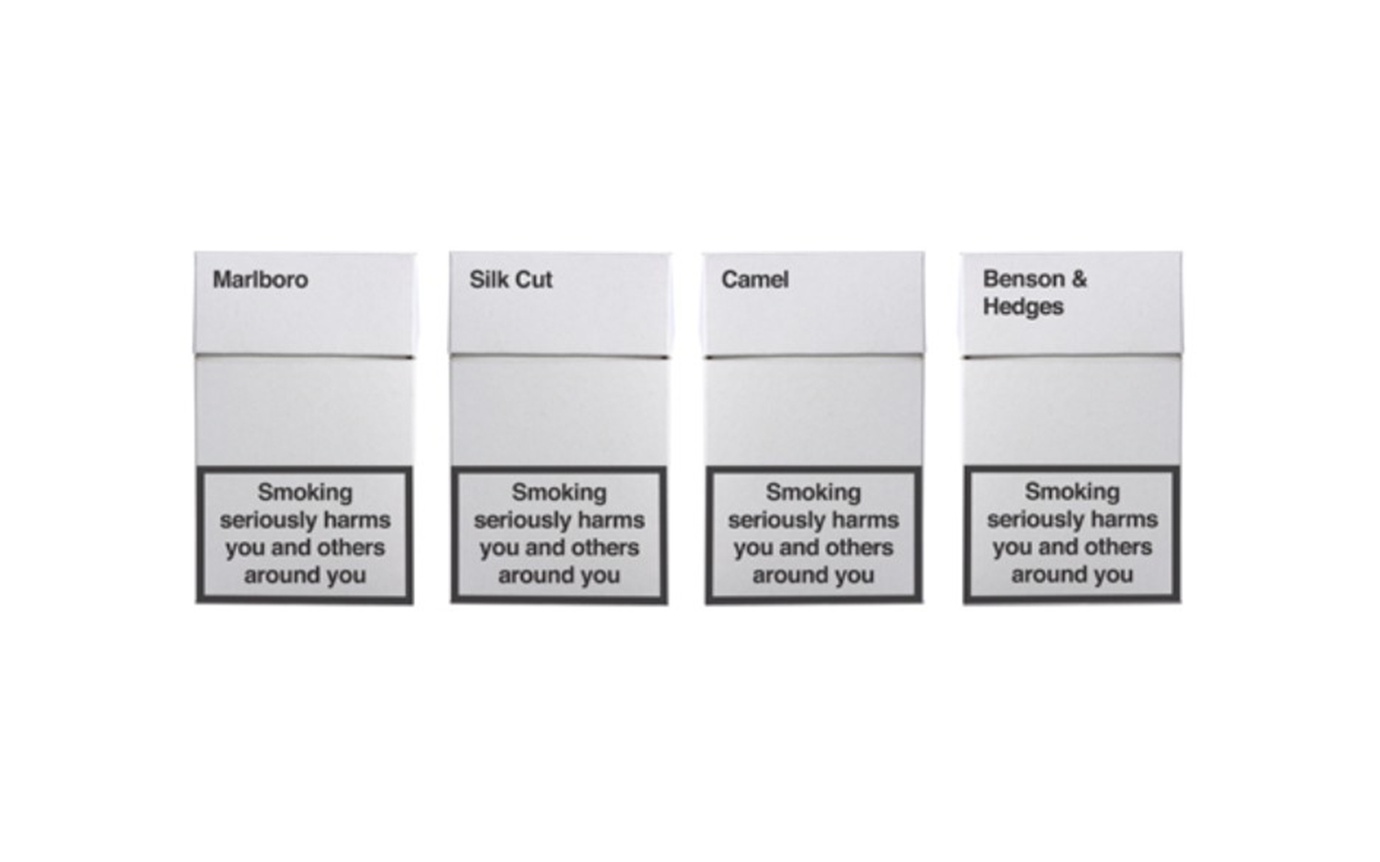

From a purely branding perspective, and setting aside other potential issues such as black marketeering, it is necessary to look at what packaging tells consumers – and, indeed, what consumers are looking for in the first place.

So, while the notion of plain packaging does look good in theory and helps politicians make the right noises by targeting the emotional connection consumers form with products, there is something of a special case with tobacco. The packaging regulations which are in place already have surely done all they can to create that connection: pictures of scarred lungs, cancerous lips and other horrifying imagery are included along with more traditional marketing messages.

If those images, as well as spiralling taxes on the product, haven’t stopped smokers, it’s arguable that nothing will.

Even banning cigarettes is unlikely to eliminate the habit from society; other illegal drugs such as ecstasy, methamphetamine and cannabis carry stiff penalties, yet over 13 percent of Kiwis between the ages of 16 and 64 use the latter drug regularly, with the United Nations’ 2006 World Drug Report noting that this is the 9th highest consumption rate globally.

Moreover, particularly for younger smokers, there is something of a ‘bad boy’ (or, indeed, girl) image associated with lighting up a cigarette. If this is the case, and those of us who can still recall being of that age might anecdotally confirm the theory, the gloomy pictures may actually speak directly to what the consumer is buying.

With any labelling, you need to understand who you are talking to, what they are looking for and what you are saying about your product. With cigarettes, the fact that they are bad could be the very reason that the consumer is seeking them out. Make them even worse, first by putting images of disease on the packaging, and for those consumers, the product has just stepped up a notch.

Packaged in plain wrappers, the cigarettes are now such contraband that they cannot even carry the branding that every other legal product on the market can, and cigarettes become truly ‘bad-ass’, potentially carrying the same ‘thrill factor’ as purchasing illegal drugs.

Plain packaging in Australia has not delivered clear cut results, with politicians claiming reductions in the numbers of smokers, but detailed studies such as the Davidson and Da Silva paper ‘The plain truth about plain packaging: An econometric analysis of the Australian 2011 tobacco plain packaging act’ indicate that there is no concrete proof of sales reductions.

When it comes to labelling, some universal rules apply. You need to understand what you’re trying to achieve with that labelling. You need to convey the total experience, tell the customer what the product is and what it does that is unique and what the customer wants to hear. With cigarette plain packaging, seeing that it is so dangerous that it can’t even be branded might be exactly what those customers want to hear.

Article featured on idealog